In Memoriam Ed Annink

Bright mind, beautiful ideas

On the morning of 25 September, 2012, designer and co-founder of Ontwerpwerk design studio died. He had been seriously ill for some time, but his passing away came unexpectedly nonetheless. Max Bruinsma remembers a friend.

In the 'postmodern period room' in the old Centraal Museum Utrecht stood a radiant young man with remarkably blond hair, surrounded by bizarrely shaped furniture and household utensils. Among them a vacuum cleaner by Ebbing/Haas that looked like a model of a nuclear plant and an eye-catching floor consisting of angular and undulating fragments of vinyl tiles. The young man was Ed Annink, the floor was his design as was the desk with quirky top, and the rest of the interior was selected by him from radical proposals by Dutch designers. It was the spring of 1985 and my first encounter with one of the merriest designers I have ever met. The 'period room' was a serious exercise and already vintage Annink: a provocation, not in the iconoclastic sense but to stimulate reflection on one's own patterns of expectation. By organizing the room not in a museal manner but rather more untidily, with this vacuum cleaner on the floor as if the occupant had left the premises momentarily on an errand, it looked both familiar and quite strange. Ed Annink was a master at creating productive confusion.

Was – I have a hard time getting used to the fact that he's dead. Almost 56 years old, he was by far not finished, even if he had achieved a lot. As co-founder and partner of Ontwerpwerk in The Hague, he initiated and supervised a vast amount of projects for often large commercial and institutional clients, from corporate identities to exhibitions, from books to campaigns. Parallel to his work as creative director at Ontwerpwerk Annink operated under his own name as an internationally acknowledged and most of all imaginative product designer who enduringly reveled in provoking mild confusion. 'Hare' is a good example: he transformed a small icon of a running hare by visual statistics designer Gerd Arntz, whom he greatly admired, into an almost two meters wide door mat. An intelligent jest – why, use the epitome of running away as symbol for a welcome mat? –, which was simultaneously employed for a serious and successful attempt at rekindling interest in Arntz's work. This resulted in a book and a website, which for the first time offered general public access to the complete thesaurus of around 4000 pictograms, icons and small illustrations that comprises ISOTYPE, the visual statistics system Arntz developed as designer with Otto Neurath in the 1920s and '30s.

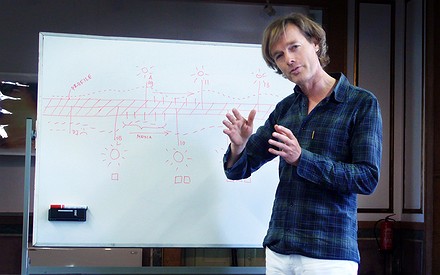

As no other, Ed Annink grasped the effect of a good combination of seriousness and fun. With a passionate debater's twinkle in his eyes he sometimes showed strange objects, merrily awaiting reactions. A tea spoon with a hole? Why, it stirs considerably better and works perfectly as a jewel as well! Besides, who uses tea spoons to actually scoop up sugar in our days of sugar cubes and sachets? Relentless logic, but barred of the doggedness many modernist employ in cementing their stance. Meanwhile, Annink was a modernist as well. He appreciated strict argumentation, also in visual form, and loved systematic design in a simple visual language.

But he was a modernist with an insatiable appetite for what's next. With his postmodern period room he also provoked himself, and he continued doing so. As founder, in 2001, of the master's course 'Experience and Entertainment Design' at the Design Academy Eindhoven, for instance. This embodied, at least for Dutch standards, a devilish combination of popular entertainment and high design. Coney Island meets Droog design. Annink was constantly working to forge such bridges between popular culture and the design elite, mass industry and exclusive design, politics and culture. The manifestation The Hague – Design and Government, in 2010 is a good example. An ambitious program in the context of The Hague's bid to become 'European Cultural Capital' in 2018, it was employed by Annink to renew the connection between designers and the government as exemplary commissioner. And to engage design as a binding factor in a multi-cultural Europe.

Annink was an energetic promoter of design as a means of interpreting the world. Design, not merely as problem-solving tool but also, and most of all, as a way of seeing. The exhibition Bright Minds, Beautiful Ideas, which he staged for the Experimentadesign biennial in Lisbon in 2003, was a passionate homage to this design mentality. A remarkable combination of work by Bruno Munari, Charles and Ray Eames, Martí Guixé and Jurgen Bey showed how these designers, in Annink's words, "question everything and are capable of coupling fantasy, playfulness and investigation with vision. They link culture to economy and science and match curiosity and openness with social commitment and action." Words that amount to a self portrait of Ed Annink.

Since our first encounter in 1985, I have regularly worked with Ed. In 2005 we collaborated on the exhibition 'Catalysts!' for Experimentadesign, the biennial for which we are both advisors as well. During brain storms in preparation for the next biennial, Ed could be hardly saying anything for hours at a time. He was listening and taking notes amidst the sometimes heated debates around him. Towards the end of the session, the chairwoman would ask him what he thought of it? He would answer with a short and meticulous summary of the day's proceedings and could then say: "...but what if we took a completely different look at this?" God, I'll miss that bright and beautiful man!

This post is also available in English ... reageer

Wil je reageren op dit artikel? Stuur een mailtje naar de redactie.